In my previous posts about the Viking Age, I have focused all of my attention on Norway, and in particular, on the kings and sub-kings of present-day Norway during the 9th-10th century AD. I now would like to shift the focus east, to the East Way (or Austrvegr) and the Estonian Vikings in particular.

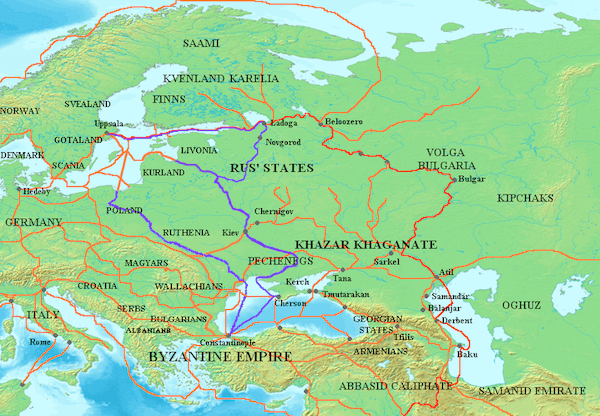

My study of the Vikings in the east has usually centered around the Viking trade routes and the Rus kingdom with its trading centers Staraja Ladoga, Novgorod (Holmsgardr), then Kyiv (Kœnugarðr), as well as on the Rus who ultimately became the royal guard of the emperors of Byzantium, known as the Varangian Guard. I completely bypassed the area that those early traders and adventurers had to sail through in order to get to the Rus kingdom and its trade routes: the Baltic area, or, as it has been referred to in old Norse, the Austrvegr (the East Way). It turns out, trading and raiding had been happening within the Baltic area and between its numerous tribes for centuries — long before the Viking Age effectively “began” in AD 793.

Research into the Baltic area shows that early contact between the peoples of the Baltic region began in the Migration Period (ca. 5th century) and probably even before. In the 6th century, contact between Estonia and eastern Sweden appears in the form of lavish ornamentation such as jewelry, clothing details, and belts, which have been found in burials from that period in the coastal area of northern Estonia and on the island of Saaremaa. Whether obtained by raiding or trade or both, we do not know.

In about AD 650, a settlement arose in Grobiņa, on the western coast of present-day Latvia, which has also been mentioned in written sources. A large cemetery has been found there, with a range of Scandinavian grave goods buried with the dead. According to an earlier interpretation, it was a colony of Svear and Gotlanders.

Around AD 750, Scandinavians established a trading center in Staraja Ladoga in the lands of the Baltic Finns. This was one of the early urban trade centers, and it arose alongside similar centers at Birka in Sweden, at Hedeby and Ribe in Denmark, and at Kaupang in Norway.

According to records from the East Slavonic chronicles, in about AD 862 the local tribes of east Estonia and present-day northwestern Russia united under the reign of three brothers of Scandinavian origin. Soon after that, one of the brothers, Prince Rurik of Novgorod, obtained sole rule over the land.

The emergence of these trade centers is not to say that relations in the Baltic area were all peaceful. Far from, if the sagas are to be believed. Though written ~300-400 years after the events occurred, Snorre Sturlason recounts several tales of warriors and sea kings fighting in the Baltic. For instance, he recounts, “Salve, son of Hogni in Njordöy,…who was at the time harrying in the Baltic.” Later, that same Salve kills King Eystein in Svealand, and puts under him the Svear. King Eystein’s son is named Yngvar. He is said to have been “often in his warships, for Sweden had been harried both by the Danes and by men from the Baltic.” After the death of King Eystein, King Yngvar gathered his army and sailed to Estland (Estonia). Ingvar came to Läänemaa (Aðalsýsla) and plundered in a place called Stein. When a superior Estland force arrived, there was a battle and the Swedish warriors were forced to flee. King Ingvar fell, and he was buried there, by the sea. King Anund, his son, later sailed to Estland and avenged his father.

In 2008, at a construction site on the Estonian island of Saaremaa, workers uncovered the remains of two Viking ships near Salme, and multiple warriors who had apparently died in battle some time around AD 750. The ships were riddled with arrowheads, and all of the warriors had died a violent death. Was this the site called Stein to which Snorre refers, or was this just another battle scene in the Baltic? We may never know.

Our final story also comes to us from Snorre Sturlason. In it, he tells us about Olaf Tryggvason, the son of King Trygvi Olavsson, who had been killed by Harald Greycloak after the death of Hakon (or Haakon) the Good. Fearing they might suffer a similar fate at the hands of Harald, Olaf and his mother flee Norway and sail for Novgorod, where Olaf’s uncle is serving in the army of the prince. The ship never reaches its destination. Estonian Vikings capture the ship and enslave Olaf, his mother, and various members of the crew. Olaf spends six years as a thrall in Estonia before being discovered and rescued by his uncle at a marketplace.

What all of these stories tell us is that tribes were traversing the Baltic for centuries before the Viking Age officially began, seeking wealth and adventure, or simply looking to barter for needed items. What’s more, sea kings, warriors and Estonian Vikings were fighting for land and their share of the wealth all through the region. Perhaps, then, it would be more accurate to say that the Western Viking Age began in 793, but the Eastern Viking Age had already been going on for centuries.

Thanks for reading!

Sign Up

Sign up to have new blog posts and other free content delivered to you monthly!